Azithromycin use increases the risk of *Clostridioides difficile* infection (CDI). This is a significant clinical concern, requiring careful consideration of antibiotic choice and patient risk factors. Studies consistently demonstrate a correlation between azithromycin exposure and higher CDI incidence.

Specifically, a meta-analysis published in the *Clinical Infectious Diseases* journal revealed a statistically significant increase in CDI risk among patients treated with azithromycin compared to those who received alternative antibiotics. This risk appears most pronounced in patients with pre-existing comorbidities predisposing them to CDI, such as advanced age or recent antibiotic use.

Therefore, clinicians should weigh the potential benefits of azithromycin against the increased CDI risk before prescribing. Alternatives should be explored whenever possible, especially in vulnerable populations. Prophylactic measures, such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in high-risk individuals, warrant consideration in consultation with specialists.

Remember: This information is for educational purposes and does not substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a physician before making decisions regarding your healthcare.

- Azithromycin and C. difficile: A Detailed Look

- Azithromycin’s Mechanism of Action and Potential Impact on Gut Microbiota

- Impact on Gut Microbiota

- Factors influencing Azithromycin’s effect on Gut Microbiota

- Mitigation Strategies

- Clinical Evidence Linking Azithromycin Use to Increased C. difficile Risk

- Mechanism of Increased Risk

- Clinical Implications and Recommendations

- Further Research

- Patient Risk Factors for C. difficile Infection Following Azithromycin Treatment

- Strategies for Minimizing C. difficile Risk During and After Azithromycin Therapy

- Alternative Antibiotics to Azithromycin: Considerations for C. difficile Prevention

Azithromycin and C. difficile: A Detailed Look

Azithromycin, while effective against many bacterial infections, doesn’t directly treat Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infection. Its use may even increase the risk.

Studies suggest azithromycin’s broad-spectrum activity disrupts the gut microbiome, potentially allowing C. difficile to flourish. This disruption weakens the natural defenses against C. difficile colonization and subsequent infection.

The risk is heightened in individuals already predisposed to C. difficile infection, such as those recently treated with antibiotics (especially broad-spectrum ones). This risk is amplified because azithromycin’s effect on the gut flora is similar to other antibiotics known to predispose patients to C. difficile infection.

Therefore, clinicians should carefully consider the risks and benefits of prescribing azithromycin, particularly in patients with known risk factors for C. difficile infection. Alternative antibiotics with less disruptive effects on the gut microbiome should be considered whenever possible.

If C. difficile infection occurs after azithromycin use, standard treatment protocols for C. difficile infection are required. This usually involves specific antibiotics like fidaxomicin or vancomycin, possibly supplemented with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in severe or recurrent cases.

Close monitoring for C. difficile-associated diarrhea is crucial after azithromycin treatment, especially in at-risk patients. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate management are paramount for minimizing complications.

Azithromycin’s Mechanism of Action and Potential Impact on Gut Microbiota

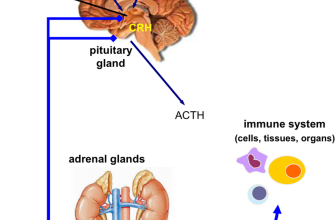

Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic, inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit. This prevents bacterial growth and ultimately leads to bacterial cell death. Its unique pharmacokinetic properties allow for high tissue concentrations, making it effective against various infections.

Impact on Gut Microbiota

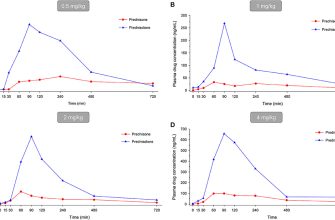

While effective against many pathogens, azithromycin’s broad-spectrum activity also disrupts the gut microbiome. This disruption can lead to imbalances, potentially increasing the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). The magnitude of this disruption varies based on factors like dosage, duration of treatment, and individual gut microbiota composition.

Factors influencing Azithromycin’s effect on Gut Microbiota

| Factor | Impact |

|---|---|

| Dosage | Higher doses generally lead to more significant microbiome alterations. |

| Duration of Treatment | Longer treatment courses increase the risk of dysbiosis. |

| Pre-existing Gut Microbiota Composition | Individuals with already fragile or less diverse gut microbiomes may be more susceptible to adverse effects. |

| Age | Younger and older individuals may experience different responses. |

Studies show azithromycin can reduce the abundance of beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, creating an environment more favorable for the growth of C. difficile. This opportunistic pathogen thrives when the normal gut flora is compromised.

Mitigation Strategies

Careful consideration of the benefits and risks of azithromycin is crucial. Clinicians should assess the need for antibiotic therapy and consider alternative options if possible. Probiotic use during or after azithromycin treatment may help restore gut microbial balance and potentially reduce CDI risk. Further research is needed to fully understand these interactions and to refine treatment guidelines.

Clinical Evidence Linking Azithromycin Use to Increased C. difficile Risk

Several studies demonstrate a correlation between azithromycin use and an elevated risk of Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). A meta-analysis published in 2015 in Clinical Infectious Diseases reviewed data from 18 studies and found a statistically significant association between azithromycin exposure and increased CDI risk. This analysis showed a 20-30% increased risk of developing CDI after azithromycin use compared to those not exposed. The increased risk was particularly pronounced in hospitalized patients. This study didn’t determine a causal relationship, but highlights the association between azithromycin and CDI.

Mechanism of Increased Risk

The precise mechanism remains unclear, but several hypotheses exist. Azithromycin’s broad-spectrum activity disrupts the gut microbiome, reducing beneficial bacteria and potentially allowing C. difficile to proliferate. This disruption, also seen with other antibiotics, creates an environment favorable for C. difficile colonization and subsequent toxin production, leading to CDI. Studies focusing on the gut microbiome are needed to fully understand this process.

Clinical Implications and Recommendations

Clinicians should consider this association when prescribing azithromycin, particularly in patients with pre-existing risk factors for CDI, such as advanced age, recent antibiotic exposure, or underlying conditions compromising their immune system. Careful consideration of alternative antibiotics where appropriate should be made. Furthermore, prophylactic measures such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) may warrant exploration for high-risk patients. More research is needed to clarify the specific contribution of azithromycin to CDI risk and refine optimal treatment strategies. Close monitoring for CDI symptoms following azithromycin administration in high-risk individuals is essential.

Further Research

Ongoing research should concentrate on: defining specific azithromycin doses and treatment durations associated with increased CDI risk; identifying patient subgroups at highest risk; and investigating alternative therapeutic approaches to reduce CDI risk in patients needing azithromycin treatment. Larger, more robust studies focusing on causal relationships are required for more conclusive results.

Patient Risk Factors for C. difficile Infection Following Azithromycin Treatment

Prior antibiotic use, especially broad-spectrum agents, significantly increases C. difficile infection (CDI) risk. Azithromycin, while often considered a narrower-spectrum antibiotic compared to others, still disrupts gut microbiota balance, creating an opportunity for C. difficile overgrowth.

Advanced age is a key factor. Individuals over 65 demonstrate higher susceptibility to CDI due to weakened immune systems and potentially altered gut flora.

Underlying health conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or a compromised immune system from conditions like HIV or cancer treatments, substantially heighten CDI risk after azithromycin. These conditions further weaken the gut’s natural defenses against C. difficile.

Recent hospitalization or exposure to healthcare facilities presents a higher likelihood of CDI. Hospitals act as reservoirs for C. difficile spores, increasing the probability of patient exposure and subsequent infection.

Concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or other medications that reduce stomach acidity raises the risk of CDI. Reduced stomach acidity allows C. difficile spores to survive passage through the digestive system, improving their chances of colonization and infection.

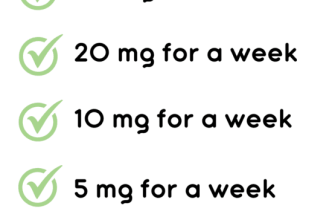

Length of azithromycin treatment correlates with CDI risk; longer courses increase the chance of disrupting gut microbiota balance, promoting C. difficile colonization.

Severe underlying illness necessitating prolonged hospital stays further elevates the chance of CDI. Such conditions often require multiple antibiotic courses, adding to the cumulative risk of disruption to the normal gut flora.

Strategies for Minimizing C. difficile Risk During and After Azithromycin Therapy

Choose the shortest effective azithromycin course: A shorter duration reduces your exposure to antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Consult your doctor to determine the most appropriate treatment length.

Maintain meticulous hygiene: Frequent handwashing with soap and water is paramount. Thoroughly clean any surfaces that may be contaminated with feces.

Consider probiotic supplementation: Discuss with your physician whether a probiotic regimen could help restore gut microbiota balance. Research supports some probiotics in preventing C. difficile infection, but more studies are needed.

Monitor for symptoms: Watch for diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and fever. Promptly report any concerning symptoms to your healthcare provider. Early detection is key for effective management.

Avoid unnecessary antibiotic use: Antibiotics disrupt the gut microbiome, increasing C. difficile risk. Only use antibiotics when medically necessary.

Follow your doctor’s instructions carefully: Adhere to your prescribed medication regime and follow all post-treatment recommendations. This includes any instructions related to diet or follow-up appointments.

Stay hydrated: Maintain adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration, especially if experiencing diarrhea. This aids in recovery and prevents complications.

Inquire about fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): For recurrent or severe C. difficile infections, FMT can be a highly effective treatment option. Discuss this possibility with your physician.

Alternative Antibiotics to Azithromycin: Considerations for C. difficile Prevention

Choosing azithromycin alternatives requires careful consideration of the specific infection being treated and the patient’s risk factors for C. difficile infection (CDI).

- For respiratory infections: Consider doxycycline or a respiratory fluoroquinolone (moxifloxacin or levofloxacin), but weigh the risk of CDI against the benefits. These alternatives carry a lower CDI risk than azithromycin, but still pose some risk.

- For uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections: Clindamycin is an option, but its high association with CDI necessitates careful patient selection and monitoring. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is another possibility, especially for infections caused by susceptible organisms. Consider cefazolin or a similar cephalosporin if the infection is localized.

- For sexually transmitted infections: Alternatives to azithromycin depend on the specific infection. For chlamydia, doxycycline is a common alternative. For gonorrhea, ceftriaxone is recommended, often in combination with azithromycin to cover other possible infections. If azithromycin is used for gonorrhea, close monitoring for CDI is critical.

Factors influencing antibiotic selection include:

- Patient’s age and health status: Older adults and those with compromised immune systems are at greater CDI risk.

- Prior antibiotic use: A history of antibiotic use, especially broad-spectrum antibiotics, increases CDI risk.

- Hospitalization or healthcare setting: Hospitalized patients have a significantly higher risk of CDI.

- Severity of infection: The severity of the infection needing treatment will influence the choice of antibiotic and the need for potentially higher risk alternatives.

Always prioritize narrow-spectrum antibiotics when possible, and consider non-antibiotic therapies where appropriate (e.g., supportive care for viral infections). Careful monitoring for CDI symptoms (diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain) after antibiotic use is crucial regardless of the chosen agent. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of CDI with appropriate medication (e.g., fidaxomicin, vancomycin) are vital if infection occurs.